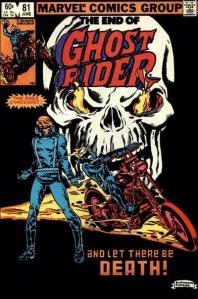

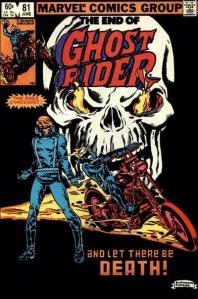

In the early 1980s, one of my favorite comicbook series was Marvel Comics’ Ghost Rider, which centered around itinerant motorcycle stuntman Johnny Blaze, a man cursed to share his body with a demon he could barely control.

Johnny Blaze first appeared in Marvel Spotlight #5 (Aug. 1972) and subsequently spun off into his own 81-issue series, which ran from 1972-1983. I first learned about the series when I saw #58 on a spinner rack at Perry Drugs. I opened up the first page and read the “Stan Lee presents…” caption and thought it was “cute” that this flaming skull character was called Johnny Blaze.

Ghost Rider #58, the issue that, for me, started it all.

I bought the issue and every one after that until the series ended. I really liked how— especially as the series grew closer to the end— Ghost Rider developed into a metaphor of a man dealing with his personal demons. The more often Johnny Blaze became Ghost Rider, the more the demon within him— Zarathos— was able to gain independent control when he was Ghost Ridering. As a result, the Ghost Rider went from being an extension of Johnny’s personality to someone Johnny had to fight in order to keep the demon from getting too far out of control. Zarathos was Johnny Blaze’s personal demon on both a literal and metaphorical level. Like the alcoholic seeking “just one drink”, Johnny was often tempted to give in to the desire to become Ghost Rider because it was an “emergency.”

In issue #68, while sitting in a confessional, Johnny admitted that he sometimes wanted the Ghost Rider to get out, to “give the guilty what they deserve.”

Ghost Rider #68. Johnny gives Zarathos free rein.

I eventually bought all the back issues and I have to say what ended as a great book had a less-than-great beginning. Or rather, certain elements of the early stories could have been better. in Marvel Spotlight #5, Johnny sold his soul to “Satan” (later retconned as the Marvel Comics’ character Mephisto) to save his stepfather, motorcycle stuntman “Crash” Simpson, from cancer. The bargain was struck, but Johnny forgot to say anything about Crash not dying in a fiery motorcycle accident later that same day.

Here’s one less-than-stellar part about the early issues: Later that night, “Satan” comes to collect Johnny’s soul, but is prevented from doing so by Roxanne Simpson because she’s “pure in heart.” So he gives Johnny the Ghost Rider curse instead. Right. The idea that Roxanne’s “purity” could keep “Satan” from taking Johnny— more than once— makes no sense. If her purity is so powerful that it protected Johnny even when she wasn’t actually around, why didn’t it, say, prevent “Satan” from striking a deal with Johnny in the first place?

It’s also obvious that in the early days Ghost Rider was just a way to cash in on the then-popularity of both motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel and The Exorcist. In and of itself, that’s not a bad thing, but the later internal battle between Johnny and Zarathos made for better stories than those about a supernatural “superhero.”

Late in the run, we learned that hundreds of thousands of years ago, Zarathos was powerful and feared, until Mephisto made the demon his slave. From time to time, he’d merge Zarathos with the soul of a human. Johnny Blaze was the latest to receive this “gift”, though in many ways it was an “up yours” to Johnny in retaliation for Johnny having gotten free of his contract.

In the end, Johnny was freed of Zarathos and got a happy ending.

That wouldn’t last, of course. When Marvel launched a revised Ghost Rider series centering around teenager Dan Ketch in the 1990s, Johnny Blaze soon showed up. Dan wasn’t hosting Zarathos, but he and Johnny did have a connection. Eventually, a somewhat complex mythology involving a centuries-old Ghost Rider lineage would develop, most of which I only know about from reading a book called Ghost Rider the Visual Guide by Andrew Darling (I stopped reading the Dan Ketch series after 24 issues).

Johnny has since returned in several miniseries, some of which I’ve read and some of which I haven’t, as well as an ongoing series that ran from 2006-2009. I read and liked the first storyline in that series, but I prefer how Johnny’s original series ended. He defeated both his literal and metaphorical demons and got to go on with his life. Why saddle him with the Ghost Rider curse again?

Maybe Johnny Blaze had an impact on later writers, to the extent that they opted to use him again rather than just stick with Dan or introduce some new character.

By the way, I’m not the only one who felt that the internal struggle gave both the title and the characters a certain appeal. The final issue of the 1972-1983 run of Ghost Rider contains an essay by writer J. M. DeMatteis called “Travels with Zarathos or Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye.” In that essay, DeMatteis, who came on board as writer with issue #74, wrote that one thing that drew him to Johnny and Zarathos is that the latter was, “the personification of man’s eternal grappling with the evil within.”

Exactly. Johnny’s internal struggle is one thing that made Ghost Rider great in its last several months.

DeMatteis also pondered where the series might have gone had it continued. He pointed out that Zarathos, personifying Evil, was the catalyst in Blaze’s transformation from self doubt to certainty and self awareness, perhaps even self assurance.

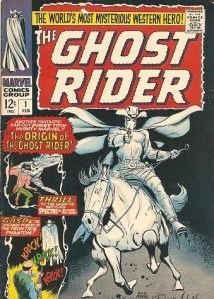

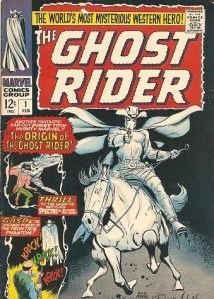

A movie version of Ghost Rider starring Nicolas Cage as Johnny Blaze and Eva Mendes as Roxanne Simpson appeared in 2007. It conflated elements of both the Johnny Blaze and Dan Ketch series. It also made the non-supernatural Western Ghost Rider character, who pre-dated Johnny Blaze, a part of the same mythos. In the comics, school teacher Carter Slade (originally Marshal Rex Fury in a 1950s Ghost Rider series published by Magazine Enterprises before Marvel published its western version in 1967) used theatricality to give the impression he had supernatural powers. In the film, Slade was the same type of Ghost Rider as Johnny Blaze.

The Carter Slade Ghost Rider in the comics.

And in the film.

In the movie, Johnny’s father, Barton Blaze (Brett Cullen), is dying of cancer, not Crash Simpson. And Johnny— a teenager at the time (Matt Long)— doesn’t summon the “Devil”/Mephisto. Instead, Mephistopheles (Peter Fonda) comes to him. What’s more, Johnny never actually agrees to the deal. He’s just looking at the contract (which is in Latin) when it cuts him and spills his blood on it. He should have hired a lawyer. Given how the legal system works, the case would have been tied up for millennia.

Also, in the film, Johnny first becomes the Ghost Rider decades later, not the night he makes the deal.

The movie had both good and bad points and a sequel, Ghost Rider Spirit of Vengeance, was released in 2012.

When the 2007 film came out, I expressed a hope that a sequel would show at least something of the internal conflict between Johnny and the demon within him. I finally got around to watching Ghost Rider Spirit of Vengeance earlier this month (for the record, it’s not as good). While it established that the demon within Johnny was Zarathos, it didn’t address an internal struggle between the two. It did, however, state that Zarathos had originally been an angel of justice who was tricked, captured, brought down into Hell, corrupted and driven insane.

It’s implied that by the end of the movie the “spirit of justice” aspect of Zarathos has been reawakened. If there’s ever a third film, Zarathos’ definition of justice might not match with Johnny’s, leading to conflict between the two.

If there’s ever another Ghost Rider film— whether a third in this series or a reboot— I’d hope it would address the internal conflict between Johnny Blaze and Zarathos on top of whatever external foes he/they face. It’d be a more interesting than if he just fought bad guys.

Johnny Blaze’s original adventures can be read in The Essential Ghost Rider Vols. 1-4. The stories are reprinted in black and white, but the volumes are affordably priced.

Copyright 2015 Patrick Keating